Editor’s Note: And one last review of the comics of 2/13/2013 before the comic stores open with the new books…

Editor’s Note: And one last review of the comics of 2/13/2013 before the comic stores open with the new books…

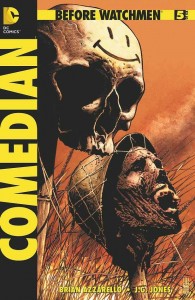

I had sworn to myself that I was gonna stop reviewing Comedian by writer Brian Azzarello and artist J. G. Jones, because after just two issues I knew it wasn’t working for me, and even that damnation with faint disappointment was only possible when the book wasn’t actively pissing me off.

From the beginning, Azzarello has made Comedian a story where Watchmen continuity is optional on a good day, where consistency of character with any prior depiction of Edward Blake was problematic, and where Azzarello seemed less interested in telling a story about The Comedian than he did in telling a story about shit that happened in the 1960s where The Comedian happened to be. Sure, The Comedian was an active part of the story, but it wasn’t so much about him; imagine Mad Men if Don Draper was selling anti-Kennedy ads to Donald Segretti, or if he was running a pro-segregation focus group with James Earl Ray as a member: all of Mad Men‘s elements are there, but it ain’t really a story about a conflicted advertising executive anymore, is it?

That tendency continues in Comedian #5, which, as per this book’s norm, is less a story about The Comedian than it is a story about Vietnam and My Lai, where The Comedian just happens to be. Which, again, I’ve learned to expect from this comic book, and which is something that I didn’t think needed further reviewing. However, Azzarello added one thing to this books that boiled my blood. It’s not much – just two words – but to my mind, it put a stamp on the book stating Azzarello’s intentions toward the book, and it’s a check that the series just doesn’t cash. And while there’s a possibility that I’m wrong, and that those two words might just be a simple Easter Egg to observant readers or maybe a nod to placing Comedian into a Wold Newton-style shared universe, it blew me out of the book as effectively as would have seeing Blake throwing the meat to Trudy Campbell. Or even Pete Campbell.

Blake and fellow soldier Benway are stranded in the Vietnam jungle, trying to find a spot for evacuation and talking about a prior massacre of a village of locals, including the women and children. While picking their way through booby traps and local terrain, Blake justifies the attack (using liberal use of flashbacks) via a philosophy that it is better for America’s enemies to fear it than love it, and that if someone is not America, they are the enemy. As Blake makes his way to the helicopter, the CIA is recommending that Blake be pulled from Vietnam and his actions covered up, while Presidential candidate Richard Nixon makes sure that certain information about Blake makes it’s way to his buddy Bobby Kennedy.

This story has next to nothing to do with The Comedian. It is about Vietnam, and more importantly, about American attitudes toward war from Vietnam through pretty much Iraq and Afghanistan; The Comedian merely acts as Greek Chorus to give voice to the attitude, as Azzarello seems to see it. Between Blake’s comments to Benway calling the enemies animals, and his comments during the massacre flashbacks that it’s okay to kill civilians so that the enemy knows we’re not pussies, he gives a particular viewpoint to justify the extreme opinions that can justify everything from village burning in Vietnam to indiscriminate bombings in Cambodia to drone strikes in Afghanistan. And this kind of thing is fine, as far as I’m concerned; I have no problem with creators using comics to call attention to or be critical of real world issues, but here, Azzarello basically uses sililoquy from Blake to flatly say what Azzarello wants us to hear. Sure, we get some visuals of the atrocities of war, but we also get The Comedian saying, “You know what I was originally gonna call myself? The Big Stick,” which, as subtle allegories go, isn’t one. It is the epitome of Tell Don’t Show, and it makes the book more simplistic preaching than it does a good comic story.

And then there are those two words, where Azzarello seems to want to put himself on a level that nothing in Comedian can even remotely justify. And those words, comprising the signature on the CIA memo recommending that Blake be pulled from active duty and his actions covered up, are “Raul Duke.” That name being a bastardization of Hunter S. Thompson’s fictional byline and alter ago in Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas, Raoul Duke. Now, whether it was intentional on Azzarello’s part or not, by effectively namechecking Hunter Thompson, who wrote powerfully and extensively about the 1960s, Azzarello is implicitly inviting comparisons between Comedian and Thompson’s pantheon. And frankly, it was a sly little move that made me crazy with rage; I am a huge Hunter Thompson fan, and to see a comparison invited between, say, Fear And Loathing On The Campaign Trail or The Great Shark Hunt and a comic story where a dude just flat-out says obvious stuff to drive a point home regardless of character or continuity just made me angry. Those two simple words – that one name- turned a simple disappointing comic-reading experience into one that actively pissed me off.

J. G. Jones’s art is the high point of this issue; as usual, he uses a fine line to produce photorealistic figures and faces that are extremely expressive, and his celebrity depictions, from Bobby Kennedy to G. Gordon Liddy, are spot on… although his Nixon is only shown at distance and recognizable by his rotten hairline. Jones depicts violence in a fairly horrifying and realistic manner, which is key to hammering home the horrors of modern war that Azzarello is attempting to decry in this issue. With that said, I had a problem with the visual storytelling here; this book jumps back and forth between the current attempt to escape the jungle and the flashback of the village attack, and there are no visual cues to indicate what timeframe you’re looking at at any given time. With a simple jungle background and a bunch of guys in uniform, there aren’t any obvious visual cues to tell you if you’re seeing present or past. If you do the old Jim Shooter test of looking at the art without reading the words to see if you can still follow the story, this issue fails. Now, not all of that is Jones’s fault, since the script clearly calls for the jumping back and forth, and any use of color cues to indicate timeframe would fall to the colorist, but I found the visual storytelling to be far more confusing than it needed to be.

Comedian #5 just isn’t that good a comic book. The storytelling is simplistic, and seems to be secondary to Azzarello using the title character to spew a viewpoint to which he seems to be hoping to call negative attention. It’s a story about Vietnam and modern war in general, which is a hell of a thing for a book with The Comedian’s name on the cover. But the namecheck of Hunter Thompson, who wrote about Vietnam and the 60s more effectively than just about anyone, was simply infuriating to me. Sure, maybe Azzarello was trying to wink at a shared universe where Doonesbury’s Uncle Duke is in charge of Blake’s file… and maybe that’s the best way to read this issue. Because otherwise, I’m forced to compare Comedian #5 to, say, Hell’s Angels. And that’s not a war anyone can win.

Podcast RSS Feed

Podcast RSS Feed iTunes

iTunes Google Play

Google Play Stitcher

Stitcher TuneIn Radio

TuneIn Radio Android

Android Miro Media Player

Miro Media Player Comics Podcast Network

Comics Podcast Network