EDITOR’S NOTE: All the atoms in the test chamber are screaming at once. The spoilers… the spoilers are taking me to pieces.

EDITOR’S NOTE: All the atoms in the test chamber are screaming at once. The spoilers… the spoilers are taking me to pieces.

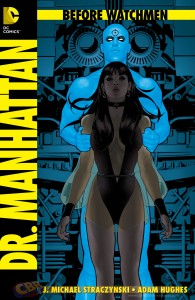

I’ve mentioned this before, but I think it bears repeating: Adam Hughes’s Dr. Manhattan #1 cover looks like the Good Doctor is blasting Silk Spectre right in the shitter.

Now that we have the pleasantries out of the way, we can talk about the issue itself. And a big part of me expected to not like this book. Writer J. Michael’ Straczynski’s work on fellow Before Watchmen title Nite Owl has been disappointing on a good day, and an irritating retcon of various elements of Watchmen continuity as a whole, on a bad one. Further, this book lives and dies based on Manhattan’s preoccupation on quantum theory, which is something that I can’t remember the character ever obsessing over in Watchmen, but which makes sense since Wikipedia’s article on quantum mechanics shows that not only was quantum theory viable in the mid 20th century, but that even in the early 21st century I am still too stupid to understand quantum theory.

With that said, this is an engaging book that captures the ADD nature of Dr. Manhattan’s inner dialogue in a manner that Watchmen fans will find familiar, fills out some of the backstory to the character that makes some sense, and closes on an intriguing mystery that makes me want to come back to see how it plays out. At the same time, it also somewhat overplays those character traits in ways that don’t make sense for a character who can see the totality of time, instills motivations on Manhattan that have never been mentioned before, and uses the word “box” more than an 1974 porno loop.

That’s the hell of quantum mechanics – all possibilities are real, and influenced by the observer.

The issue focuses on Dr. Manhattan, everywhere, at all times… which makes it the first comic book where I almost literally can’t tell you what’s happening, because everything is happening. We bounce from Manhattan on Mars as in Watchmen #4, to his childhood, to Gila Flats, back to Mars, back to college. In the process, we get a sense of what John Osterman was like as a child (spoiler alert! Timepiece-obsessed friendless dink), in college (spoiler alert! Timepiece-obsessed sexless dink), and his obsession with control through the whole span of it. That obsession leads Manhattan to travel back in time, to before he, as Osterman, was trapped in the Intrinsic Field Generator, to try and determine how he was trapped in it when he was so sure he had time to get out… with interesting and unexpected results. Oh – and he also alters quantum probability itself to chuck his Nathan’s Coney Island Blue Hot to Silk Spectre. But we’ll get back to that.

Manhattan’s perspective, as shown in the internal dialogue captions, is a pretty solid match to how Moore presented it in Watchmen #4. Straczynski presents Manhattan’s viewpoint as fluid in time, narrating what he’s thinking about while Hughes changes the visual to a different time period that still matches the narration. For example, he has a conversation with the original Nite Owl end on the phrase, “can’t control everything” as the panel switches to a view of clockwork, and a scene where it becomes apparent that young Jon Osterman couldn’t close the deal with a girl if he had a team of lawyers on his side. Moore was the master of this kind of storytelling, but Straczynski delivers it well enough that the flow feels like authentic Dr. Manhattan.

I was less enthralled with some of what that narration told me, which was that Jon Osterman was an introverted control freak obsessed with clocks and seemingly unable to communicate with people. In Watchmen, we’re shown a young Osterman playing around with his dad’s old watch just for practice before his father throws it away so Jon can focus on nuclear physics… and we never see him with another watch until he tells Janey he can fix hers… just before they do the dirty boogie in a Coney Island hotel room. Further, Stracyznski gives us the previously-mentioned sequence where Jon is reassembling a watch while in college, and a hot blonde comes in to hit on him, almost literally jamming her tits in his face (Hughes even shows us Jon’s point of view through a jeweler’s loupe, which really accentuates those honkers, just in case we’re not getting the point)… and Jon sends her away. Considering that we readers have a 25-plus year understanding that Jon uses his watchmaking skills to score with women, this just didn’t ring true to me.

Now, with that said, the characterization of Dr. Manhattan as a long-time control nut makes a certain amount of sense – one might argue that it would take a detail-obsessed OCD case to rebuild himself a body after being disintegrated. But in order for this particular story to work, we need to accept that Manhattan is motivated by his need for control; in this comic, it drives him to rig the drawing as to which member of the Crimebusters he will be paired up with (in a retelling of the same sequence Strazcynski put into Nite Owl #1, where Captain Metropolis draws Rorschach’s name, and Manhattan alters it to be Silk Spectre’s), it drives him to spend his pre-Manhattan life rebuilding clocks instead of living life, and it drives him to go back in time to see what really happened in his accident. Which is a perfectly good motivating factor for the things that happen in this book… but I’m sorry, that isn’t Dr. Manhattan.

Throughout Watchmen, Dr. Manhattan is presented as the most passive character of the bunch. As the world edges toward Armageddon, he fucks off to Mars. When presented with a riot, he merely sends everyone home. When involved in almost any discussion, he refers to the things that he knows are about to happen, and simply allows them to occur. And a lot of this is based on Manhattan’s perception of time: both Moore and Straczynski acknowledge that Manhattan can see the totality of his experiences through time as a single, linear experience. Further, Moore has Manhattan, more than once, acknowledge that Manhattan not only knows the future, he knows that he is powerless to change it. Things happen, Manhattan knows they are going to happen, and he simply goes with the flow, so to speak.

Even before Osterman is turned into Manhattan, Moore shows the character as passive, simply allowing things to happen to him. In Osterman’s first meeting with Janey in Watchmen #4, Osterman tells her, “Well, you know… my dad sort of pushed me into it. That happens to me a lot. Other people seem to make all my moves for me.” That is not the manifesto of a character obsessed with control.

So to believe that Manhattan is a control freak, willing to alter quantum realities by fucking with cards to wind up with Laurie, and willing to push backwards in time to experience his own creation regardless of any consequences, simply doesn’t jibe with the character’s history. Dr. Manhattan is not active. He wound up with Laurie because she noticed him at the Crimebusters meeting; he would never actively change what he knows is going to happen. And frankly, a passive guy who winds up with the first woman who buys him a beer and who spends ten years studying nuclear physics because his dad told him to? That guy puts down the watch and goes to the lake with the blonde with the big jugs… because she made the first move.

Hughes’s art in the book is excellent, as it always is, although I’ve always found it kind of ironic that a guy who has a reputation for doing cheesecake art (remember the Mary Jane statue?) got the nod to do pencils on a book where the protagonist spends a large percentage of his time dangling wang. His stuff is realistic – sometimes almost apparently photo referenced – with a mix of thin and thick lines. His figures are realistic (but, in accordance with his normal reputation, the women are less realistic than spectacular), and his reproduction of elements from the original Watchmen like the photo of Osterman and Slater that Manhattan takes to Mars, as well as his depiction of historical figures like John Kennnedy, are excellent. Hughes also demonstrates the effect of Manhattan’s change of the card to pair with Silk Spectre by spinning the panels after that event into two stacked branches, showing some of the potential effects on either side of the decision. It’s cool stuff.

But I also want to give a nod to colorist Laura Martin, who brings a ton of cool little additions to the art. The pages that show Manhattan’s past not only have a dulled, sepia-toned palate in the images, but the pages themselves carry that color in the gutters between the panels, making the page look old, and which really accentuates the feeling of being in the past. Martin adds a bunch of additional nifty little touches, like making nine-year-old Osterman’s birthday present – the object that introduces the recurring quantum theme of Schrodinger’s Box – in Dr. Manhattan Scrotum Blue. The mix of images and colors make this one of the most interesting-looking Before Watchmen books so far.

All in all, this is one damn pretty book, and the mix of narration and point of view are solid and in tune with Moore’s original character depiction. And the cliffhanger ending is interesting enough for me to come back to see where Straczynski’s going with it. But for Watchmen purists – and I am one of them – Straczynski’s depiction of the character of Dr. Manhattan is fatally flawed. Manhattan as control-obsessed simply does not jibe with Moore’s characterization, and while it works – and is necessary – in Stracynski’s story, it simply isn’t Moore’s Manhattan. If you can put that aside, you’ll dig this book. If you can’t, you won’t.

Huh… that means that the book is both alive and dead. Schrodinger would approve.

Podcast RSS Feed

Podcast RSS Feed iTunes

iTunes Google Play

Google Play Stitcher

Stitcher TuneIn Radio

TuneIn Radio Android

Android Miro Media Player

Miro Media Player Comics Podcast Network

Comics Podcast Network