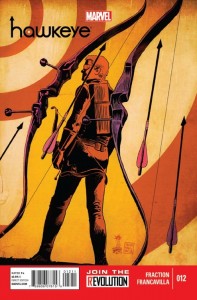

I normally try not to review the same title two months in a row unless it’s a big event comic – my reviews take a while to write thanks to my congenital case of diarrhea of the keyboard, and there are only so many hours in the day – but what the hell can I tell you? Hawkeye #12 is just that Goddamned good.

I normally try not to review the same title two months in a row unless it’s a big event comic – my reviews take a while to write thanks to my congenital case of diarrhea of the keyboard, and there are only so many hours in the day – but what the hell can I tell you? Hawkeye #12 is just that Goddamned good.

Seriously, I don’t know how Matt Fraction ever got this series greenlit without having photos of Axel Alonso in a compromising position with some form of beast of burden or something. Hawkeye barely appears in this book. There are exactly four panels of bow and arrow action. The closest thing to a supervillain is a Russian cocksucker in a tracksuit. The closest thing to a superhero battle and strategy is when a guy decides that he’s earned that money the Russians offered him in exchange for letting them kick the shit out of him. And this is in a Marvel superhero comic; for contrast, imagine a Superman comic that was about Jimmy Olsen getting ripped to the tits on laudanum while bemoaning his childhood by letting strange women pay him to take a dump on his chest.

This kind of superhero comic simply shouldn’t work; describing it on paper makes it sound like an inventory fill-in issue by a writer who was instructed to turn in something that doesn’t directly fuck around with the main character’s status quo. But it’s not like that at all; instead, we get a solid show-don’t-tell character study of Clint’s brother Barney, a snapshot of Clint and Barney’s childhood that uses artist Francesco Francavilla’s skills to show us a lot of information without having to waste a lot of time with unnecessary exposition, and for me, the first time I’ve ever seen a reason I can believe why Clint wouldn’t just write his brother – a Dark Avenger who stole Clint’s Hawkeye identity only weeks ago – completely off. All without seeing Hawkeye for more than a single page.

It shouldn’t work. But it does. Because it’s a superhero story about people, with some of the best pulpy art you can find anywhere.

We have doubled back in time to the timeframe of the last issue, where we followed a dog who was investigating a murder (yeah, photos of some form of farm animal. It has to be). Clint’s brother, who is down on his luck and down to a handful of change, has called and asked to meet. While he waits for the appointed time, Barney tries panhandling from the Russian “bro” gangsters who are following Clint (and omnipresent in Hawkeye), who instead offer him escalating amounts of money… in exchange for taking an escalating level of beatings. Meanwhile, Barney reminisces about a bucolic childhood with Clint, provided your definition of “bucolic” is very different from mine and somehow refers to feces in some way, where Clint had all the heart in the world but none of the size to back it up, and Barney had to teach him how to fight. Cut back to the present, where Barney learns the hard way that you can’t trust a Russian in a tracksuit, and takes steps to correct their attitudes.

Up until now, Barney Barton has always just kinda been the anti-Hawkeye that’s been dragged out now and again to give Clint a one-to-one matchup, and whose entire reason for being seemed to be jealousy of Clint and his straight, hero life. This issue blows that pretty much out of the water. Fraction, in just 20 pages, turns Barney into an honest-to-God brother, one that any guy who has a brother can recognize. We see the long-time catchphrases between them, how each of them know what the other is like, and, with the flashbacks, how their relationship was forged through the adversity of a really shitty childhood. I didn’t grow up that way, but as a guy who moved a bunch of times as a kid, I can recognize how sometimes it can feel like you and your brother against the world, so the nature of the relationship between the two kids, even into adulthood, rang true to me.

Most interestingly, Fraction shows us that Barney is more forward and emotionally outgoing than Clint in childhood and in adulthood, and that really goes a long way toward illustrating out Clint’s personality. As children, Barney’s the one trying to teach Clint how to fight, how to control his temper until he gets bigger, and how to work on his aim, all in an impossible situation… and Clint doesn’t say a single Goddamned word through all of it. At least not until the end, when we finally see what happened to their parents, when Clint says one word… and with that word, we learn a lot about what’s going under the hood with that guy. Combine that with the fact that it’s Barney reaching out to Clint as an adult, and this issue gives the reader a real sense that, while Clint might be the hero in this relationship, maybe he’s not the good guy.

The overall effect is to give us a realistic-feeling relationship between two adult brothers. Like I said: I have a little brother, and despite those childhood feelings of sometimes being me and him against the world, we are really not all that close anymore. So seeing Clint and Barney trying to talk uncomfortably on the phone while relying on old jokes and gags, while remembering how it was when they were kids, really hit home for me. Not enough to, you know, pick up the phone and talk to my brother, but nonetheless: if you’re anything like me and my brother, there’s gonna be a lot in this issue that speaks to you.

I’ve never pretended that Francesco Francavilla wasn’t one of my favorite artists working right now, and I’m not gonna pretend differently now. His pulp sensibilities work really well for a story that focuses on down-and-out guys and cheapjack gangsters in the alleys of New York, as well as in the random violence of the Barton’s busted home out in the sticks somewhere (realistically, we learn all we need to know about the circumstances of Clint’s and Barney’s childhood from Francavilla’s depiction of their clapboard house with the rusted-out late-60s Chevette (or maybe Impala or even Camaro – either way, it’s old American muscle rolling iron) in the yard. His layout is in a simple grid, with two exceptions: the one real action scene where Barney decides to push back against the Russians, and the splash where Clint’s and Barney’s parents meet their fate. And that splash is Goddamned masterful; with a single image and a couple of details thrown into the image of broken glass, Francavilla tells us not only what happened and why, but help to hammer home the true nature of the Barton’s patriarch. Bottom line: while I’ve been enjoying David Aja’s art on Hawkeye and don’t want to see him leave, I sure would like to see Francavilla come back for the odd issue now and again.

Hawkeye #12 is, as almost all issues of Hawkeye have been, a superhero book without a superhero. It’s a book almost without its title character. It should be a mess… but it’s not. It is a human story about two brothers, which makes it damn relatable to anyone who isn’t an only child or was born in a vat or something. It also tells us a lot about Clint, and why he is the way he is, even without showing Hawkeye almost at all. It’s a weird superhero book, but that’s okay: it’s not about superheroes. Check it out.

Podcast RSS Feed

Podcast RSS Feed iTunes

iTunes Google Play

Google Play Stitcher

Stitcher TuneIn Radio

TuneIn Radio Android

Android Miro Media Player

Miro Media Player Comics Podcast Network

Comics Podcast Network